Tags

animals, blessing, interconnected, Jesus, poor, Sermon, St. Francis, stigmata, yoke

Today we honor the life and witness of St. Francis of Assisi. St. Francis is well-known and beloved for myriad reasons. Primarily, people tend to appreciate two things about him: his commitment to living in solidarity with the poor, which included dramatically stripping his clothing off, begging for food, and supporting the most needy; and, his affinity for the creatures of God, with stories of preaching to birds, negotiating with a violent wolf to make peace with the local town, and generally valuing the beasts of the earth. But what we rarely talk about is the stigmata of St. Francis – those marks corresponding to the ones left on Jesus’ body by the crucifixion said to have been impressed by divine favor on devoted followers of Christ.

Here’s what we know about St. Francis’ stigmata. He was praying on the Feast of the Cross, which falls on September 14. His prayer that day to Jesus was that he might feel in his body and soul the pain that Jesus felt in the Passion. But he also prayed to feel in equal measure the excessive love that Jesus felt that allowed him to endure pain for us. We are told that in his intense prayer session, he saw a vision, and when he emerged, he had what looked like piercings in his hands and feet – or, stigmata.[i] Now I don’t know how you feel about the existence of stigmata on certain saints, but I’ve always thought it was a little, well, weird – and even more heretical, maybe even unbelievable.

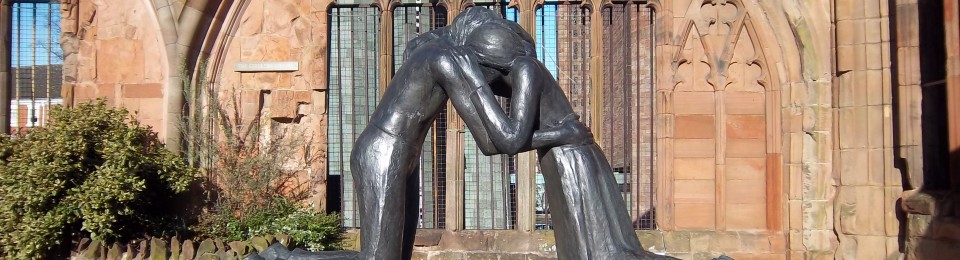

So, why, on this Sunday when all we want to do is bless and celebrate animals or remember the poor, do we need to talk about stigmata? Believe me or not, there is actually a deep correlation with today’s gospel lesson. Today, Jesus talks about yokes – those tools used to harness two animals for work. The yoke allows the two not just to double their work, but to rely on one another – if one is tired, the other can push harder; and then the weaker one can later support the stronger one. Yokes, like Jesus’ work, are easy and make the burden light.

But beyond the mechanics of a good yoke, the yoke is also a good metaphor for how we see the gospel. Being yoked to another makes you connected. And once you are connected, and see how dependent upon one another you are, you begin to see how that connection extends beyond the two of you – that your yoked interconnection is a microcosm of the connectedness of all of God’s creation. When Francis prayed fervently to both feel Jesus’ deepest physical pain as well as Jesus’ excessive outpouring of love, his resulting stigmata left a physical reminder of the ways in which, even in pain or great love, we are connected to one another.

Perhaps another example may help. “Ramakrishna was a mystic who lived in India over a hundred years ago. One day, as he was walking through the marketplace, he saw a servant boy being whipped by his master. As he watched that boy being whipped, welts appeared on Ramakrishna’s own body.” We are told that, “This suggests that this man had such a strong feeling for this boy that he could identify with him in the sufferings that he was enduring.”[ii] Furthermore, “Like Ramakrishna, who was so at one with God that he could walk through the marketplace and become one with God’s creations, especially this poor servant, Francis so identified with the suffering of Jesus that he took on the wounds himself.”[iii]

What we see in Francis’ stigmata and even in the experience of the mystic Ramakrishna is that when we are living faithfully, we begin to see that we are yoked to one another. We slowly begin to see all of humanity is connected. And the more we spend time seeing the humanity in others – especially the humanity in those we would rather not – then we start to see that our interconnectedness extends even further – to God’s creation, to God’s creatures, to the cosmos. If we open our hearts to one, we cannot help to open our hearts to all. Francis’ love for the poor, Francis’ love for creatures, and even Francis’ stigmata are not disconnected – they are one in the same.

In Psalm 148, a psalm sometimes read or sung on St. Francis’ feast day, we hear an invitation to all of God’s creation: Mountains and all hills, fruit trees and all cedars; Wild beasts and all cattle, creeping things and winged birds; Kings of the earth and all peoples, princes and all rulers of the world; Young men and maidens, old and young together.[iv] We bless animals today because Francis reminded us how all of God’s creation is worthy of love and is interconnected. But the invitation for us today is not just to love on cute dogs, cats, hamsters, and horses. The invitation for us is to start claiming our yoked nature – yoked to those we love, yoked to our political opponents, yoked to those who have different ethics and values than ourselves, yoked to parents who make different parenting decisions, yoked to those with different skin color or sexual orientation or gender identity, yoked to those we see as deserving of God’s grace and those who are not. Our yoked nature allows us to pray the Prayer of St. Francis from our Prayer Book: “Lord, make us instruments of your peace. Where there is hatred, let us sow love; where there is injury, pardon; where there is discord, union; where there is doubt, faith; where there is despair, hope; where there is darkness, light; where there is sadness, joy. Grant that we may not so much seek to be consoled as to console; to be understood as to understand; to be loved as to love. For it is in giving that we receive; it is in pardoning that we are pardoned; and it is in dying that we are born to eternal life.”[v] We can do the work of St. Francis because of the yoke of Jesus. Thanks be to God. Amen.

[i] Hilarion Kistner, O.F.M., The Gospels According to Saint Francis (Cincinnati: Franciscan Media, 2014), 88-91.

[ii] Kistner, 87-88.

[iii] Kistner, 92.

[iv] Psalm 148.9-12.

[v] BCP, 833.