Tags

church, community, darkness, death, failure, Good Friday, Jesus, light, love, relationship, Sermon, sin

There is something about Good Friday and the passion narrative from John’s gospel that is gruelingly convicting. On most days we do a pretty good job of convincing others and ourselves that we are fine – that we are working hard, trying to love and serve others, and be a faithful follower of Christ. But if we are honest, part of what is so hard about facing Good Friday is that facing Good Friday means facing ourselves – facing our failures, our sinfulness, our lack of ability or even willingness to actually follow Jesus.

I confess that the last four months, one of my coping mechanisms for facing the state of our country has been to read, listen to, and watch less news. I was finding that my mental health was getting diminished the more time I spent reading, listening, and watching the news, so I just stopped. I filled the void with music, or people, or movement, but not with knowledge. That has been my method of coping, to shut out the ugly, painful, and evil, because the alternative has felt overwhelming – so overwhelming that I can scarcely put together words around my devastation about who and how we have become, especially as people of faith.

But coming here, listening to John’s words, engaging in the Good Friday liturgy feels like the exact opposite. Listening to that passion narrative feels like standing in an ocean of sinfulness, failures, and all that is not of God, and having waves of devastation hit us over and over and over again. If we are really listening and really being honest with ourselves, all of the bad of this story is not bad that others do – but bad that we have all done at some point in our lives. We grieve over Judas because we too at times have thought we knew better than Jesus and took matters into our own betraying hands. We grieve over Peter because we too have prioritized our survival instinct over faithfulness. We grieve over Caiaphas because we too have argued our way through the ethics of choosing the lesser of two evils instead of not choosing an evil at all. We grieve over Pilate, seeing how hard he tried to do the right thing, because we too have caved under peer pressure and fear. We grieve over the chief priests who are caught up in anger and the desire to remove a thorn from their sides because we too have often wished that someone difficult would just go away. We grieve over soldiers who follow orders even when they know they are doing wrong, because we too have towed the company line.[i]

Coming to church on Good Friday is our way of turning the news back on, sitting in the ashes, being fully and honestly ourselves in ways that we rarely do because doing so is painful, vulnerable, and scary. But doing so also opens us up. When we allow ourselves to face the fullness of human depravity – the fullness of our own depravity that we try so desperately to hide – we open up a path in the darkness to the light. We agree to this exercise of turning on the news because we trust that the Church can empower us into another way – can help us find light and life in the ocean of darkness and death.

When I was training to become a priest, I spent a summer serving as a chaplain in a hospital. The days were long, and you never knew what situations would be thrown at you – from folks making their way through routine surgeries, to people in the ICU unable to communicate what landed them there, to people holding vigil with a beloved (or dreaded) family member. I remember one day in particular getting paged up to a floor for someone approaching death. When I arrived, the nurses told me the family had left for the day, but the patient of the family would likely die in the next hour. The family lived further than an hour away, and had asked that someone sit with her in their stead. The nurses had decided I was that someone. And so, I sat, with someone whose story I did not know, whose faith and piety was unknown to me, and, at that point, with no knowledge of what the moment of death actually looked like. And so I sat, uncomfortably called to a task I felt completely ill-equipped for, and yet, by my identity as Christian, was called to perform.

In that horrible ocean of Good Friday, there is light in our darkness. Despite all those faithful people who failed Jesus so horrifically and fully, four people hold vigil. They show up. They stay. And, eventually, by doing exactly what you are doing today – sitting in the inconceivable darkness of Good Friday – they see a glimpse of light. Three Mary’s (Mary, Jesus’ mother, Mary wife of Clopas and sister of Mary, and Mary Magdalene) and the beloved disciple stand near the cross. They do not protest, they do not fight, they do scheme. They hold vigil by Jesus, facing the evil of the crucifixion of the Messiah, and they stay. They do not run away, they do not cover their ears or eyes, the do not try to mask the ugly in something pretty. They bear witness together, gathering at the foot of Jesus’ cross, staying fully open to the awfulness of the cross.

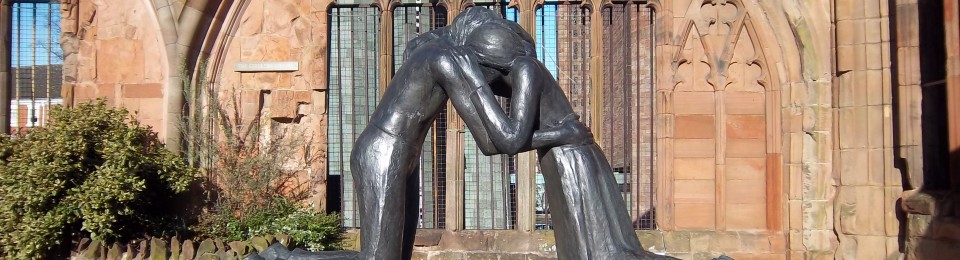

In that moment of gathering – of not really doing something other than being present – something transformative happens. Jesus says some of the words we label as the Last Words of Jesus. Jesus says to his mom, “Woman, here is your son.” And then he says to the beloved disciple, “Here is your mother.” What commentators say about these words is that Jesus created the new family unit with these words. Now, I get a little skittish when we call church communities families because families are so incredibly complicated and the term “family” can be so loaded – often with negative connotations. Instead, I might say that, in his abandonment and death on the cross, Jesus creates a path of light – a way to find companionship, community, and Christ – through relationships with Jesus at the center. Peter Gomes describes the moment beautifully. He says, “…what we find…is Jesus redefining the concept of family: What it is, who belongs, and what it does. It should not surprise us that here on the cross…he now reorganizes human affections. He redefines human relationships, creates a new family, and in the center of it is to be the remembrance of him. This is a family that is made not by blood, not by the old way, but by love and care: that is the new way.”[ii]

On the one hand, this new definition of our relationships is beautiful in and of itself, and perhaps that beauty can sooth all the grief we talked about surrounding this scene. And, on the other hand, there is a charge in this gift, in this path of light. For months I have been trying to figure out what the call to us as Christians is at this time – especially for the “family” or “community” here at Hickory Neck that is so diverse in its political expression. What unites us, that community that we have formed for centuries gathering around the common table is found in this moment in Good Friday. In the turmoil and divisiveness of this time, Jesus reminds us that we are obligated to one another. We are parents and children. We are lovers and loved. Even, and especially, with those people with whom we have no blood connection to – we are bound to one another in Christ. And it matters when members of our gifted community are being persecuted, are being made afraid, are being made “other” – are essentially being booted out of our community of love. In this turbulent time, we cannot run off, we cannot avoid, we cannot seek the lesser of evils. We can gather at the cross and bear witness – bear witness to the encompassing love of Christ and the community to whom we are now obligated to love too. In a world where we may feel like there is no way, Jesus breathes words of love and life into every one of us – words that cannot be contained in our own lungs and hearts and souls.

I do not know where this path of light in the darkness will take us. I do not know how Jesus is calling you to be mother or father or son or daughter. I do know that even in the darkest of days, Jesus sees light in you. Jesus sees goodness in you. Jesus see possibility in you. And if we have nothing left to celebrate, we can walk out of here today commissioned in love and light. Amen.

[i] Jim Green Somerville, “Pastoral Perspective,” Feasting on the Word, Yr. C, Vol. 2 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 300, 302.

[ii] Peter J. Gomes, The Preaching of the Passion: The Seven Last Words from the Cross (Cincinnati: Forward Movement Publications, 2002), 32