Tags

community, faith, God, grasp, lesson, life, money, parenting, Sermon, share, sympathize, value, vocation

Parenting is probably the most difficult of the vocations God has given me – not simply because parenting can be physically, emotionally, and spiritually exhausting, or because of the heftiness of the responsibility of shaping decent human beings who will have an impact on the world, or because parenting forces you to justify every belief and value you hold. Those alone would be daunting enough. But parenting is also a difficult vocation because of the way parenting evolves: from those early days of helping this creature learn the basics for survival, to those young days of helping children wonder and ask the big questions of life, to those middle days of clarifying family, faith, and individual values that will guide their behavior and choices, to those later days of gently reflecting on those ultimate things of life – of what really makes for a life of meaning and purpose.

In many ways, our scripture lessons lately have felt like listening to a parent trying to help us figure out what this whole life thing is all about. On the surface, our lessons today are straight of central casting for a stewardship talk – we’ve really teed up the parishioner who will share his testimony today with everything he needs. From Amos who foreshadows what will happen to those who spend their lives luxuriating in lavishness, as if luxuriating is an end in and of itself; to Paul’s letter to Timothy who warns how dangerous a love of money can be, distracting us from things of ultimate significance; to our gospel lesson which starkly depicts the eternal significance of how wealth can make us so blind to the needs of others that we condemn ourselves in the life beyond this life. The lessons this week seem to serve up the ultimate stewardship sermon: the place of money in our lives is so fraught with spiritual consequences, you should just give that money to the church so that you do not have to worry about a fate like those in our lessons today!

And while our budget for next year might appreciate such a lesson, much like parenting has varied phases, so does the church’s teaching of us. The one line of all the weighty lessons on wealth from today that has been hovering in my mind comes from Paul’s first letter to Timothy. In the last line of the portion of his letter we heard today, Paul says we “are to do good, to be rich in good works, generous, and ready to share, thus storing up for [ourselves] the treasure of a good foundation for the future, so that [we] may take hold of the life that really is life.” So that we may take hold of the life that really is life. The verb in the Greek translated as “take hold” is a not a gentle verb – taking hold is better translated as to grasp desperately.[i] So we are to grasp desperately to the life that really is life.

This is the phase of parenting where I find myself: how do I teach my children what the “life that really is life” is? In a world that very much feels like the passage from Amos, telling us that “life that really is life” is a life so comfortable you can set your goal as luxuriating in peace, or in a world that so values individualism that we are trained not to let our gaze linger on people like Lazarus or to even know their name for that matter, or in a world that seems to jump from one political controversy to the next, destabilizing our moral compass, how are we supposed to even know what the life that really is life is?

Award winning journalist Amy Frykholm, inspired by that simple phrase “the life that really is life,” traveled to a tiny city in southern Mexico, Fortín de las Flores, after reading Sonia Nazario’s book Enrique’s Journey. The book details the story of a Honduran man trying to make his way into the United States by traveling on top of a freight train. His story is not all that unique – the 20,000 residents of Fortín see people like him all the time. What is unusual about Fortín is how they respond to these migrants. Instead of responding with fear, or with self-protection, or even with a blind eye, the people of Fortín act as a place of mercy. Actively making their way to the trains to deliver food, water, and supplies every day – food left over from their food trucks which are just barely making enough for their own families to survive, water poured into zipped baggies they can toss them to the tops of trains, and even sweatshirts or winter hats because they know that after the stop in Fortín, the migrants will face the brutal cold of a trip through mountains. When journalist Frykholm asked them why they cared for these strangers, most of the residents just looked at her like she was asking a silly question. A resident of Fortín who had lived in the United States understood her confusion. He said, “‘The central value of this society is compartir,’ [the Spanish word for “sympathize”] …as he carried a bag of oranges toward a train that had briefly stopped not far from the hotel. ‘Even a business is primarily a place from which to share.’”[ii]

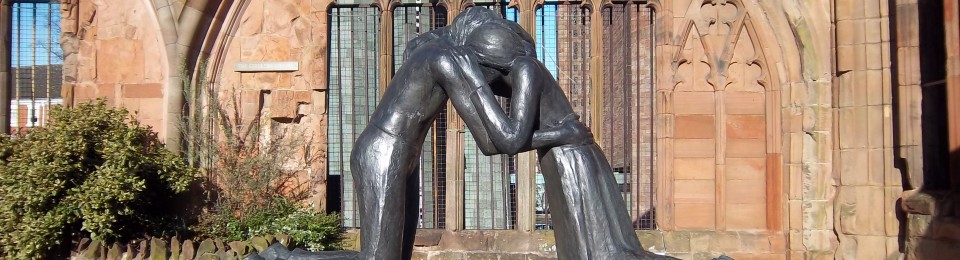

The wealth the rich man has in our gospel lesson is not bad in and of itself. The wealthy man is not even an evil man – he does not actively do anything bad to people like Lazarus. The danger in the wealthy man’s life is how he does not see,[iii] how he presumes his wealth is simply a blessing for him to enjoy from God. Debie Thomas writes, “It has taken me a long time to recognize how insidious this notion of ‘blessing’ really is. How contrary [the notion of blessing] is to Jesus’s teachings. When I was growing up, no one ever told me that by locking human suffering out, I was locking myself in. Locking myself into a life of superficiality, thin piety, and meaninglessness. As our reading from [Paul’s letter to Timothy] puts it this week, the refusal to confront my own privilege, the refusal to bear the burdens of those who have less than me, is a refusal ‘to take hold of the life that really is life.’”[iv]

That is our invitation today – to desperately grasp on to the life that really is life. Fortunately, scripture does not give us this hefty command like a parent sending out their grown child with one last bit of advice. Paul wrote this letter not just to Timothy but to the community of faith. Paul wrote this letter to the community of faith because Paul knew they could not grasp desperately to the life that really is life without some companions on the journey – without a village of people whose central value is compartir. We gather with people every week because we need a community who can hold us accountable to our values and who can challenge us when loose track of what a life that really is life is. Sometimes the community will do that by looking at us like we are asking a silly question; sometimes the community will do that by inviting us to be generous givers; and sometimes the community will do that by sitting us down to open up wisdom for us. But mostly, the community will partner with us because each one of us is desperately trying to grasp onto that life that really is life too. Together, we create our own little Fortín right here in Toano, witnessing with simplicity the life that really is life – together. Amen.

[i] Stephanie Mar Smith, “Theological Perspective,” Feasting on the Word, Yr. C, Vol. 4 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Pres, 2010), 110.

[ii] Amy Frykholm, “Life That Really Is Life,” September 21, 2025, as found at https://journeywithjesus.net/essays/3969-life-that-really-is-life on September 26, 2025

[iii] Charles B. Cousar, “Exegetical Perspective,” Feasting on the Word, Yr. C, Vol. 4 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Pres, 2010), 119.

[iv] Debie Thomas, “The Great Chasm,” September 22, 2019, as found at https://journeywithjesus.net/essays/2374-the-great-chasm on September 26, 2025.