Tags

choice, darkness, distance, envy, forgive, God, Jesus, prodigal son, relationship, responsible, right, Sermon

Having studied family systems, and living in a nuclear family with three first-born children, I am keenly aware of, if not wholly empathetic to the older brother in the story we traditionally call that parable of the prodigal son found in Luke’s gospel. This is such a complex, intriguing story, that our attention is often focused just by naming this parable “The parable of the prodigal son.” But a seminary professor once warned me that what we call parables highly influences our understanding of them. I think that is why this year, being so captivated by the older brother, I might rename this story what scholar Rolf Jacobson calls the story: The Lament of the Responsible Child.[i]

By renaming this parable The Lament of the Responsible Child, we immediately are able to reconsider his story – perhaps not as the petulant stick in the mud, but the justifiably angry family member. The older son has done what has been expected of him. He is obedient, hard-working, and would have never insulted his father as deeply as his younger brother does. He is the consummate good and faithful servant. And so, when his father, who, by the way, has never given much praise for the older son’s obedience, throws a party for his wayward brother, the older son finally snaps. He throws a first-class temper tantrum, refusing to come into the party and then yells at his father about the injustice of such a party.

What is so visceral about the older son is we know his reaction all too well. Two strong emotions take over the older son. First, he is struck with a serious case of envy. The older son sees the party for his wayward brother, and covets the party. Out of respect of family tradition and cultural mores, he never asked for even the smallest of parties for himself and his friends. But even responsible children get sucked into envy’s power. I remember when our girls were younger reading one of the Berenstain Bears children’s books call the “Green-Eyed Monster.” In the book, Brother Bear is celebrating his birthday, receiving gifts. Sister Bear is mostly fine with this arrangement, remembering her own birthday party earlier in the year. That is, until Brother Bear gets the most beautiful, sleek bicycle she has ever seen. Then the Green-Eyed Monster takes over. But just so that the adults do not think they are immune, before the story ends, Papa Bear gets a visit from the Green-Eyed Monster too when a neighbor gets a fancy new car. The point is that envy and jealousy are all too familiar to us.

But envy isn’t the only emotion that takes over for the responsible child. The other emotion that takes over is self-righteous indignation. The older son is legitimately right about his younger brother. His younger brother did sin, was disrespectful, behaved selfishly, and disgraced the entire family. The younger brother does not deserve the reception he receives. That is exactly what makes the reception so full of grace. But the older son is so blinded by his self-righteous indignation, that he cannot see the blessing of his father’s reaction. As one person describes his situation, the older brother is “standing outside in the dark, perfectly right and perfectly alone.”[ii] Perfectly right, and perfectly alone.

When I conduct premarital counseling with couples, we talk about the ways that spouses and partners behave in disagreements. Every family and couple has them, and so our counseling focuses on handling disagreements in healthy ways. I once had a priest tell me that the three most important words for any marriage are, “I. Am. Sorry.” They sound like three words that are simple enough to say. But, somehow, we have a hard time saying them. Partly we struggle with saying them because we think they mean admitting guilt or, even worse, defeat. Very few of us like to lose. But that same priest told me, the next three most important words are, “You. Are. Forgiven.” As hard as apologizing can be, sometimes forgiving can be even more difficult. But forgiveness is the only thing that can keep our relationships in balance. Ideally, by one person saying, “I am sorry,” and the other saying, “You are forgiven,” both parties give up some of their power. Both parties submit something of themselves to the other. When one party is unwilling to say one of those things, they become like the responsible child – perhaps perfectly in the right, but also perfectly alone in their rightness.

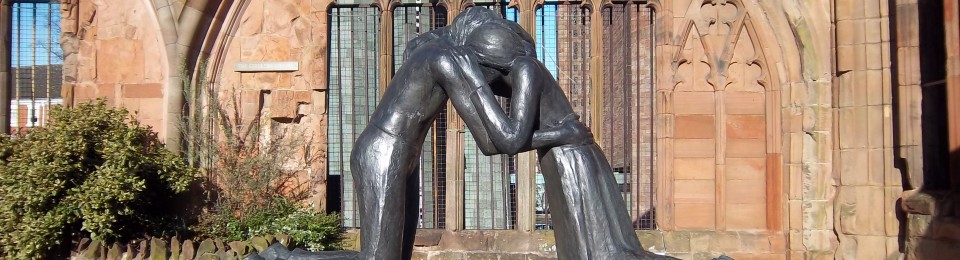

What the older brother teaches us is that sometimes we have a choice between being right and being in relationship. In some ways, much like the younger son has been in a distant country, the older son is also in a distant country. He has cutoff connection to his brother, to his father, and even to those who have gathered to rejoice over the new life his brother has been given.[iii] In choosing to be right, he stands out in the darkness, unable to rejoice in another’s joy, closed off to the hope of redemption and reconciliation. In endless paintings, woodcuts, and sculptures of this scene, whether Rembrandt, Jan Shoger, or Margaret Adams Parker, the older son stands at a distance, hands or arms crossed in front of him, cold and rigid. Artists capture what our minds have already imagined – the guarded, distant body language of one choosing rightness over relationship.

Perhaps why the responsible child’s story is lingering with me is because we do not know how he responds to the father’s invitation – the invitation into his joy – to celebrate a reconciled relationship – much like the reconciliation the older brother can enjoy if the older brother just comes into the room. The story ends with the ultimate cliffhanger that does not let you know whether the older son remains outside the party or comes inside the party. Certainly the father’s desire is for him to come in, but we do not know whether the son chooses rightness or relationship. I have wondered what would happen if the older brother went into the party. What if the younger brother fell at his brother’s feet too, saying those three hardest words, “I am sorry.” What if the two men simply embraced – saving words for later. What if the joy and laughter of that room cracked through the older brother’s tough exterior, and warmth began to seep into his heart. What if…

In many ways, I think the story ends openly to remind us that we too have a choice. We too can choose to be right – to hold on to the things in life about which we are justifiably angry and disappointed. We have every right to protect ourselves and even our family and friends from the kinds of behaviors that hurt us emotionally. We can be guarded and keep our distance – standing out in the darkness of rightness. Or we can choose to come into the party, and see what happens. We may not be able to say “I am sorry,” or even, “You are forgiven,” but we can at least step through the door, into the warm glow of a room that is bursting with abundant grace and love for us and for all – that place where all are forgiven and all are loved. Amen.

[i] Rolf Jacobson, as shared on “Sermon Brainwave: #1014: Fourth Sunday in Lent (C) – Mar. 30, 2025,” March 11, 2025, as found at https://www.workingpreacher.org/podcasts/1014-third-sunday-in-lent-c-mar-30-2025 on March 27, 2025.

[ii] Barbara Brown Taylor, “The Evils of Pride and Self-Righteousness,” Living Pulpit, vol. 1, no. 4, O-D 1992, 39.

[iii] David Lose, “Preaching the Prodigal,” March 3, 2013, as found at https://www.workingpreacher.org/dear-working-preacher/preaching-the-prodigal on March 27, 2025.