At some point in life, most of us have the experience of having a best friend. Perhaps we met the person on the playground as a child; maybe we met him in college or at work; perhaps our best friend is a cousin or sibling; or maybe our best friend is our spouse or partner. Regardless of how we met her, that best friend has seen the best and worst of us. He has congratulated us when we got a part in the play, when we got a promotion, or when we found new love. She has consoled us when we failed a test, when our heart was broken, or when a family member died. He has seen us laugh so hard that we snort or pee in our pants, and he has seen us sob so hard that snot runs down our faces. She has seen us dressed to the nines, and she has seen us in our stained, ill-fitting sweats. And our best friend has taken the best and the worst from us too: we have danced together, yelled at each other, confessed our darkest secrets to each other, and, yes, we have even hated each other at times. Despite having experienced the very best and very worst of us, we know that she loves us deeply, he always forgives us, and she is always there for us. The relationship is far from perfect, but the relationship is beautiful.

In many ways, the relationship we have with our best friend is similar to the relationship we have with God. On our good days, we come to God with our thanksgivings and praise, offering our adoration and humility to God. On our bad days, we are angry and curse God. We confess things to God that we confess to no one else: both those things done and left undone, but also those deep longings and desires that we do not admit to others. We have cried a thousand tears with God and we have laughed with great mirth. Although our best friend knows us better than any other human being, God knows even the stuff we are embarrassed or afraid to share with that best friend. And since our Lord is not human, God’s forgiveness does not know the limits of human forgiveness. Through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, our relationship with other human beings will never quite equal our relationship with God.

Given that intimacy, I am often surprised when people ask me about prayer. Throughout my ministry I have had people ask me how they should pray, what they should say, or when or where is the best time and place to pray. I think the challenge is that most of us have some notion of what prayer should look like. We imagine the pinnacle of brayer being the Zen-like posture of monks in silent prayer. Or when someone offers a prayer, we assume we should bow our heads, fold our hands, and shush others into silence. Or when someone asks us to offer the prayer, we scramble to remember common prayer phrases like, “Holy God…Bless us, we pray…you alone are worthy…” Our prayers sound very little like our everyday speech. Sometimes, if we are feeling especially uncomfortable, we peek around the room to see what everyone else is doing. People often ask me how to pray because they do not feel like they are doing it “right,” because their usual method of prayer has become stale or dissatisfying, or because when they pray, God seems far away or even like a stranger. Or sometimes people come to me about prayer because they are overwhelmed with the suffering of the world: the poverty, the gun violence, the terror that keeps striking in places like Paris. How do we pray to God when suffering seems like an endless abyss?

In scripture today, we see Hannah pray twice. In the first occurrence, Hannah looks nothing like our notions of prayer. She has been emotionally tortured by Elkanah’s second wife, Peninnah – just like Peninnah does every year when they travel to make their annual sacrifice. Peninnah is ever fertile and Hannah is barren. And, probably because Elkanah loves Hannah more, Peninnah throws Hannah’s infertility in her face whenever she can. Meanwhile, Elkanah is acting like a wounded puppy. He does not understand why Hannah is so upset – isn’t he enough? So Hannah escapes to the Temple to pray. Her prayer is unlikely offered from a pew, while she delicately flips through a prayer book to find some pre-written prayers. Her prayer is not said reverentially, with a bowed head. In fact, she does not quietly whisper prayers to God with her eyes closed. No, when Eli, the temple priest, sees Hannah praying, he accuses Hannah of being drunk in the Temple. Now I do not know if you have ever been in the presence of a drunken person, but people who are drunk are rarely still and reserved. No, I imagine Hannah was pacing. Maybe she was waving her fists at God as the tears spilled down her cheeks. Maybe there was rage and devastation in her eyes. The text says that she is silent, but that her lips are moving. I imagine she was giving God a piece of her mind. And in fact, the text tells us that she even resorts to bargaining with God – promising to commit his life to the Temple if God gives her a male child. If Eli thought Hannah looked drunk, the scene could not have been pretty!

The second occurrence of Hannah praying today is found in the Song of Hannah from first Samuel. Here we see a very different posture of prayer from Hannah. Instead of ranting and raving in the temple, here we see Hannah giving praise to God for the deliverance of a child. Hannah is full of gratitude for her own good fortune. But Hannah’s prayer is bigger than herself too. She proclaims the Lord to be a liberator – one who frees the oppressed, brings low the privileged, honors the faithful, and cuts off the wicked. In Hannah’s personal experience with God, she is given a glimpse into the global nature of God.[i] Hers is revolutionary song because God has heard her prayer and answered her. We see a very different form of prayer from Hannah the second time than we do from Hannah the first time.

For those of you reading along with A.J. Jacobs’ The Year of Living Biblically, prayer is common topic from the author. Not a believer himself, Jacobs struggles with prayer. He does not know what to do or say. But he feels compelled by the Bible to be in prayer. One of his spiritual guides suggests that there are four types of prayer – Adoration, Confession, Thanksgiving, and Supplication.[ii] Jacobs latches on to Thanksgiving at first. He starts by thanking God for the food that has been prepared, in its many stages. As he thinks about all the stages – the earth, the farmer, the packager, the person who puts on labels, the grocery stockers, the cashier – his prayer lengthens. Jacobs also takes on intercessory prayer as a form of prayer – praying strictly for the needs of others. Jacobs confesses, “It’s ten minutes where it’s impossible to be self-centered. Ten minutes where I can’t think about my career, my Amazon.com ranking, or that a blog in San Francisco made snarky comments about my latest Esquire article.”[iii] Slowly, Jacobs’ ideas about and experiences of prayer become transformed. Prayer is not like what he thought prayer would be like.

That’s the great thing about prayer. Hannah’s first “drunken” prayer of desperation and self-pity, her second prayer of adoration and revolution, and Jacobs’ ten minutes of intercessions that keep him from being self-centered are totally different. My prayers in the car on the way to pick up the kids are very different from the prayers our Contemplative Prayer Group offers on Friday nights. And the prayers of an evangelical pastor, which are accompanied by the creative tinkling of the keyboardist to emphasize and dramatize the preacher’s prayers, are totally different from the chanted prayers of the officiant of Evensong. There is no single wrong or right way to pray. And the same person who offers eloquent, beautiful prayers in the day can be the same person who rages against God in the night.

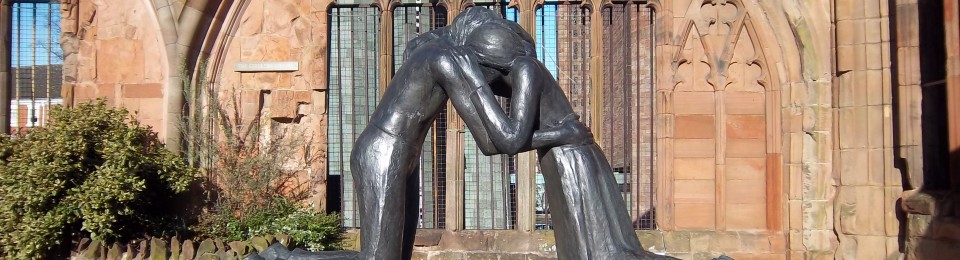

When we allow prayer to be what prayer needs to be, we let go. Then our prayers become not some preconceived notion of what we think they should be, but become a real conversation between us and the living God. Whether we are wrapped up in our own suffering, totally ceding our worries to God, or railing at God for the injustice and the inhumanity in this world, something powerful happens in prayer. Where else can we stomp our feet at God, looking like a drunkard, except at the feet of God? Ultimately, that is what is most important in our prayer life – being our honest, vulnerable, mercurial selves. As one priest explains, “…The relationship we’re offered with God is a real one. A genuine relationship. The God who made the heavens and the earth wants to know us, and wants us to know [God]. And when we’re excited, we’re to gush out like Hannah breaking out into song. And when things are falling apart, we’re to gush out like Hannah at Shiloh.”[iv] God does not care what our prayers look like or even what we say. God is just glad we show up. Our invitation this week is to show up. Amen.

[i] Kate Foster Connors, “Pastoral Perspective,” Feasting on the Word, Yr. B, Vol. 4 (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 298, 300.

[ii] A. J. Jacobs, The Year of Living Biblically (London: Arrow Books, 2009), 95.

[iii] Jacobs, 128.

[iv] Rick Morley, “Pouring Out Our Souls – A Reflection on 1 Samuel 1.4-20 & 2.1-10,” November 8, 2012, as found at http://www.rickmorley.com/archives/2052 on November 12, 2015.

In this latest season of stewardship, I reflect on the things that I can do to give back to the Episcopal Church that has provided me many fond memories; camps, dances, youth groups, just to name a few. I’ll share one memory. There was a point when I was a kid, growing up in Shelby, NC (Church of the Redeemer), that my father was out of work for an extended period of time. Mom and Dad were always active members in church (they later went on to found an Episcopal Church in Mooresville, NC – St. Patrick’s Mission). They had good friends through church, and participated in many activities. Deep into that employment transition for my Dad, the church vestry had apparently decided to use a portion of the discretionary funds available to cut a check to them, to help pay for our expenses. I’ll never forget the tears rolled down my Dad’s face when he accepted it.

In this latest season of stewardship, I reflect on the things that I can do to give back to the Episcopal Church that has provided me many fond memories; camps, dances, youth groups, just to name a few. I’ll share one memory. There was a point when I was a kid, growing up in Shelby, NC (Church of the Redeemer), that my father was out of work for an extended period of time. Mom and Dad were always active members in church (they later went on to found an Episcopal Church in Mooresville, NC – St. Patrick’s Mission). They had good friends through church, and participated in many activities. Deep into that employment transition for my Dad, the church vestry had apparently decided to use a portion of the discretionary funds available to cut a check to them, to help pay for our expenses. I’ll never forget the tears rolled down my Dad’s face when he accepted it.