Tags

baptism, belief, community, doubt, Doubting Thomas, Eastertide, faith, fear, God, incarnation, intimacy, Jesus, relationship, Sermon

For those of you who have worked with me for a while now, you know that I am easily excited by new ideas. So, when Ed and Tyler suggested the Sunday after Easter for Quinton’s baptism, I excitedly said, “Yes!” I knew we would be still experiencing the high of Holy Week and Easter from last week, I knew that baptisms are traditionally celebrated throughout Eastertide, and I knew having another reason to celebrate this Sunday would be fun. What I failed to double-check was the lectionary. As soon as I saw the gospel for today, I groaned. Who wants to talk about Doubting Thomas when we are performing a sacrament of belief and belonging?!?

At first glance, John’s Gospel text today, is in fact, a terrible text for baptism. First of all, the disciples are making a very poor showing about what the community of faith is supposed to look like. You would think after seeing the empty tomb and hearing Mary Magdalene’s testimony, “I have seen the Lord,” the disciples would be hitting the ground running, doing the work of spreading the good news, or at least throwing a raucous party. Instead, we find the disciples huddled in a locked room, cowering in fear. The text says they are afraid of the Jewish leaders, perhaps afraid the same people who killed Jesus would try to kill them too. But I think there is more to their fear. I think they are afraid to face others, because they feel they have failed. Perhaps they believe their pick for Messiah did not seem to be the Messiah after all. I think they are also behind those locked doors because they are ashamed that they failed to protect Jesus, to keep him alive.[i] Those locked doors are not just for safety – those locked doors are for hiding the shame, the disappointment, and the fear of facing others that the disciples have.

And then we have the famous Doubting Thomas. That we even call him “Doubting Thomas” is indication enough of the communal disapproval of his behavior. Why couldn’t he just believe? If not Mary Magdalene, at least his fellow disciples, who use the same words as Mary’s own testimony, “We have seen the Lord.”[ii] Even Jesus seems to disapprove when he asks, “Have you believed because you have seen me? Blessed are those who have not seen and yet have come to believe.”[iii] We do not exactly seem to be setting the stage well for little Quinton, or anyone new to the Church today.

But the more I thought about this text, and the more I read, the more I realized this is actually the perfect text for someone new to the community of faith. As little Quinton grows up, I do not want him to think that faith is about perfectly believing, perfectly behaving Christians, who perfectly go to Church. And although I want Quinton to know about doubt and to have a super healthy sense of curiosity and questioning, the truth is our labeling of Thomas as “Doubting Thomas,” gets in the way of what John is trying to teach new believers. Instead, New Testament scholar Karoline Lewis explains, “The primary definition of the term doubt, however, has to do with uncertainty. Uncertainty, as a category of belief, does not really exist in the Fourth Gospel. One is either certain or not certain; in the light or in the dark. Jesus invites Thomas to move from darkness to light, from lack of relationship to intimacy. There is no middle ground with it comes to believing in Jesus.”[iv]

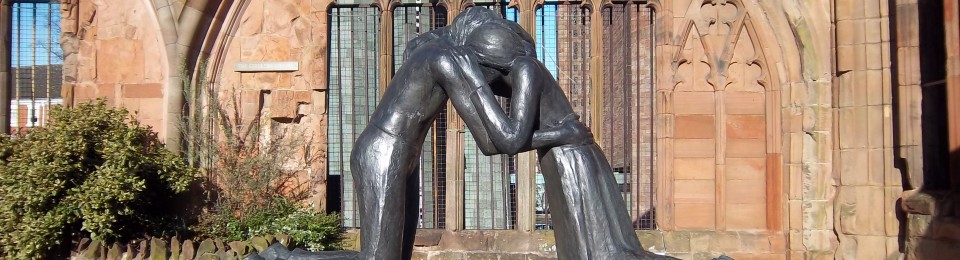

Now, stay with me on this, because I realize that dichotomy sounds even worse than doubting. Instead, what John’s gospel is doing is not about exclusion, but about radical inclusion. John is not conveying something about belief but about incarnation: “to be incarnated demands relationship. As a result, you are either in one community or another, but you cannot be not in community. Life, especially abundant life, is dependent on the reality of multiple expressions of connectivity and belonging, whether that be on-on-one or in various sizes of communities…Even God was not alone in the beginning…” So, when Thomas says, “My Lord and my God,” he is not talking about his own belief or even an individualized theology, but rather “the intimacy this Gospel imagines between believer and Jesus…” As Lewis goes on to say, “To give witness to a personal relationship with Jesus is immediately to enter into a community of intimacy between Jesus, God, the Paraclete (a fancy word for Holy Spirit[v]), and the believer and between the believer and the new community, the flock, that Jesus as the Word made flesh has made possible for the world.”[vi]

One this day, when Thomas the Twin teaches us all about what belief really means – that is, incarnate, intimate relationship with God and with one another – I cannot imagine a better word for us today. When we baptize Quinton today, we invite him into the relationships already present in this community – the real ones that sometimes cower in shame and doubt – but also the ones that lead to abundant life and blessing. When we pour water over his head and rub oil on his forehead and commit to supporting him and one another in this journey of faith, we are claiming him not as someone who will always have things figured out – because we do not always have things figured out. But we do commit to the intimacy of relationship: with the three persons of the Godhead, with one another, and with the community of faith. I cannot think of a better reminder on this second Sunday in Easter as we deepen our own intimacy with the risen Lord than to baptize and reaffirm our baptisms – as we acclaim today, “I will! (with God’s help).” Amen.

[i] M. Craig Barnes, “Crying Shame,” Christian Century, vol. 121, no. 7, April 6, 2004, 19.

[ii] Karoline M. Lewis, John: Fortress Biblical Preaching Commentaries (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014), 248.

[iii] John 20.29.

[iv] Lewis, 249.

[v] My words, not Lewis’ words.

[vi] Lewis, 250.